|

Size: 21110

Comment:

|

← Revision 51 as of 2013-04-10 23:57:11 ⇥

Size: 15074

Comment:

|

| Deletions are marked like this. | Additions are marked like this. |

| Line 1: | Line 1: |

| Take a moment and look around. Are you inside? Then you might come across books, a pile of mail, your computer and television. Or maybe you're outside, carrying your mobile device, and checking your appointments. The world we live in is surrounded by ubiquitous information. Information that is visual, audible, and tactile. It it meant to inform, to entertain, to instruct, and to warn. Because we are constantly bombarded with this information in our daily lives, we must quickly collect, filter, store, and process which of it is important to use for specific tasks. |

{{{#!html |

| Line 4: | Line 3: |

| Consider a busy intersection you are trying to cross. You are surrounded by the sights and sounds of pedestrians conversing, cars and trucks honking, birds flying, signage on billboards, and thousands of other types of stimuli. Our minds have an amazing ability to focus on the task at hand, filter the surrounding "noise," process, store, and allow us to act on only the relevant information. | <div class="saleshead"> <div class="block" id="left"> <a href="http://4ourth.com/wiki/4ourth%20Mobile%20Touch%20Template"> <div class="salesLeft"> <h3>4ourth Mobile Touch Template</h3> <p>Design for people, not pixels with this handy, wallet-sized inspection and design tool, only $10. <span>Order yours now</span></p> </div> </a> </div> <div class="block" id="right"> <a href="http://4ourth.com/wiki/Mobile%20Design%20Patterns%20Poster"> <div class="salesRight"> <h3>Mobile Interaction Design Patterns Poster</h3> <p>Every pattern from the book and this wiki, plus easy-to-follow relationships, and key information on sizes for readability and touch. <span>Order now</span></p> </div> </a> </div> <div class="salespad"> </div> </div> |

| Line 6: | Line 24: |

| When the crosswalk signal changes to "Walk," we identify the sign, interpret it's meaning, determine an action to move our body forward, carry out our actions by walking until you've crossed the street achieving your goal. Understanding how we process and filter visual information, or data, will help us design effective displays of information on mobile devices. Let’s first explore the types of information. |

}}} |

| Line 11: | Line 27: |

| == Types of visual information == All humans have more or less have the same visual processing system. However, without a standardized way of explaining and notating our perceptions, our communication of this information becomes arbitrary and not effective when designing mobile interactions. |

[[http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1449394639/ref=as_li_tf_tl?ie=UTF8&tag=4ourthmobile-20&linkCode=as2&camp=217145&creative=399373&creativeASIN=1449394639|{{attachment:wiki-banner-book.png|Click here to buy from Amazon.|align="right"}}]] == Look Around == Take a moment and look around. Are you inside? Then you might come across books, a pile of mail, your computer, and your television. Or maybe you’re outside, carrying your mobile device and checking your appointments. The world we live in is surrounded by ubiquitous information. Information that is visual, audible, and tactile. It is meant to inform, to entertain, to instruct, and to warn. Because we are constantly bombarded with this information in our daily lives, we must quickly collect, filter, store, and process which information is important to use for specific tasks. |

| Line 14: | Line 31: |

| Bertin (1977) organized visual information into two forms: '''data values''' and '''data forms'''. Ware (2000) introduces a more modern way of dividing data into '''entities''' and '''relationships'''. | Consider a busy intersection you are trying to cross. You are surrounded by the sights and sounds of pedestrians conversing, cars and trucks honking, birds flying, signage on billboards, and thousands of other types of stimuli. Our minds have an amazing ability to focus on the task at hand, filter the surrounding noise, and process, store, and allow us to act on only the relevant “signal” information. |

| Line 16: | Line 33: |

| Entities are the objects that can be visualized such as people, buildings, signs. Relationships (sometimes called "relations"), define the structures and patterns that entities share with each other. Relationships can be structural and physical, conceptual, causal, and temporal. | When the crosswalk signal changes to “Walk,” we identify the sign, interpret its meaning, determine an action to move our body forward, and carry out our actions by walking until we’ve crossed the street, achieving our goal. |

| Line 18: | Line 35: |

| These entities and relationships can be further described using '''attributes'''. These are properties of both the entity and the relationship, and cannot be considered independently. Some examples of attributes are: * Color. * Duration. * Texture. * Weight, or thickness of a line. * Type size. |

Understanding how we process and filter visual information, or data, will help us to design effective displays of information on mobile devices. Let’s first explore the types of information we will encounter. |

| Line 25: | Line 37: |

| For each of these we mean the attribute as it applies to a specific item. Not texture in general, or the texture of paper, but the texture of a specific type of paper (or even, a specific sheet of paper). | == Types of Visual Information == All humans have more or less the same visual processing system. However, without a standardized way to explain and notate our perceptions, our communication of this in- formation becomes arbitrary and ineffective when designing to display information on mobile interfaces. Ware (Ware 2000) introduces a modern way of dividing data into ''entities'' and ''relationships''. Entities are the objects that can be visualized, such as people, buildings, and signs. Relationships (sometimes called relations) define the structures and patterns that entities share with one another. Relationships can be structural and physical, conceptual, causal, and temporal. These entities and relationships can be further described using attributes. These are properties of both the entity and the relationship, and cannot be considered independently. Some examples of attributes are: * Color * Duration * Texture * Weight, or thickness of a line * Type size For each of these we mean the attribute as it applies to a specific item. Not texture in general, or the texture of paper, but the texture of a specific type of paper (or even a specific sheet of paper). |

| Line 29: | Line 56: |

| In addition to creating descriptions of our perceptions, we have also standardized a classifying way to organize them. Common classifying schemes that we use are: | In addition to creating descriptions of our perceptions, we have also standardized a way to classify them. Common classifying schemes that we use are: |

| Line 31: | Line 58: |

| * '''Nominal''' - uses labels and names to categorize data. * '''Ordinal''' - using numbers to order things in sequence. * '''Ratio''' - a fixed relationship between one object compared to another using a zero value as a reference. * '''Interval''' - the gap between two data values is measurable. * '''Alphabetical''' - using the order of the alphabet to organize nominal data. * '''Geographical''' - using location, such as city, state, country, to organize data. * '''Topical''' - organizing data by topic or subject. * '''Task''' - organizing data based on processes, tasks, functions and goals. * '''Audience''' - organizing data by user type, such as interests, demographics, knowledge and experience levels, needs and goals. * '''Social''' - a collaboration of organizing data by users who share the same interests. Such as tagging, adding to a wiki, and creating and following twitter feeds. * '''Metaphor''' - organizing data based on a familiar mental model to the user. Such as organizing computer files with folders, trash, and recycle bin. |

'''Nominal''' Uses labels and names to categorize data '''Ordinal''' Uses numbers to order things in sequence '''Ratio''' A fixed relationship between one object and another using a zero value as a reference '''Interval''' The measurable gap between two data values '''Alphabetical''' Uses the order of the alphabet to organize nominal data '''Geographical''' - Using location, such as city, state, country, to organize data. Uses location, such as city, state, and/or country, to organize data '''Topical''' - Organizing data by topic or subject. Organizes data by topic or subject '''Task''' - Organizing data based on processes, tasks, functions and goals. Organizes data based on processes, tasks, functions, and goals '''Audience''' - Organizing data by user type, such as interests, demographics, knowledge and experience levels, needs and goals. Organizes data by user type, such as interests, demographics, knowledge and experi- ence levels, needs, and goals '''Social''' - A collaboration of organizing data by users who share the same interests. Such as tagging, adding to a wiki, and creating and following twitter feeds. A collaboration of organizing data by users who share the same interests, such as tag- ging, adding to a wiki, and creating and following Twitter feeds '''Metaphor''' - Organizing data based on a familiar mental model to the user. Such as organizing computer files with folders, trash, and recycle bin. Organizes data based on a mental model that is familiar to the user, such as organiz- ing computer files with folders, trash, and a recycle bin |

| Line 44: | Line 92: |

| == Organizing With Information Architecture == Now that we are able to describe the data that we perceive, we must understand how this information should be structured, organized, labeled, and identified on mobile user interfaces. |

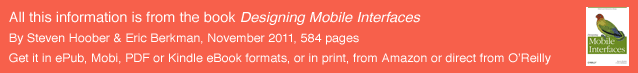

== Organizing with Information Architecture == [[http://www.flickr.com/photos/shoobe01/6501511821/|{{attachment:DisplayInfoIntro-Lists.png|Figure 2-1. Even when given pen and paper, people will make lists, so it is not surprising that lists are the most common interactive element in mobile devices. Lists can be adapted almost infinitely, for viewing or selection, for any size, and for any type of interaction.}}]] Now that we can describe the data we perceive and knowledge types we store, we must understand how this information should be structured, organized, labeled, and identified on mobile user interfaces. |

| Line 47: | Line 96: |

| One of the most common organization structures humans have used through time is a '''hierarchy'''. A hierarchy organizes information based on divisions and parent-child relationships. When using heirarchies to organize information, Peter Morville explains rules to consider (Morville, 2006): Categories should be mutually exclusive to limit ambiguity. Consider the balance between breadth and depth. When determining the number of categories regarding breath, you must consider the user's ability to visually scan the page as well as the amount of real estate on the screen. When considering depth, limit the scope to two to three levels down. Recognize the danger of providing users with too many options. | One of the most common organization structures humans have used through time is a ''hierarchy''. A hierarchy organizes information based on divisions and parent-child relationships. When using hierarchies to organize information, Peter Morville explains rules to consider (Morville 2006): categories should be mutually exclusive to limit ambiguity. Consider the balance between breadth and depth. When determining the number of cat- egories regarding breadth, you must consider the user’s ability to visually scan the page as well as the amount of real estate on the screen. When considering depth, limit the scope to two to three levels down. Recognize the danger of providing users with too many options. |

| Line 49: | Line 98: |

| Another way to organize information is '''faceting'''. In this, there are no parent-child relationships, just information attributes, like tags, which may be sorted or filtered to display the most appropriate information. The tags do not have to be explicit, and faceting may be accomplished by searching text descriptions, or even unusual methods such as searching for shapes, patterns or colors directly within images. | Another way to organize information is by ''faceting''. In this, there are no parent-child relationships, just information attributes, such as tags, which may be sorted or filtered to display the most appropriate information. The tags do not have to be explicit, and faceting may be accomplished by searching text descriptions, or even through unusual methods such as searching for shapes, patterns, or colors directly within images. |

| Line 51: | Line 100: |

| Of course, these two methods, '''hierarchy''' and '''faceting''' may be used in conjunction. A hierarchically-ordered data set can also have tags attached to it, and the facet view may combine both strict and arbitrarily ordering to display the information the user wants. | Of course, these two methods, hierarchy and faceting, may be used in conjunction. A hierarchically ordered data set can also have tags attached to it, and the facet view may combine both strict and arbitrary ordering to display the information the user wants. |

| Line 53: | Line 102: |

| Date and location are essentially special cases, and depending on the data or needs may be approached either way, even though they are strictly defined. For example, location can be an arbitrary value, with filtering or sorting for distance around a single point. Or it may be considered as a heirarchy of continent > nation > state > county > city > address. === List Navigation === A key tactical consideration, mentioned several times in the patterns, is whether browsable data sets are '''circular''' or '''dead end'''. Circular lists simply go around and around. When at the "last" item in a list, continuing to view the next item will display the first one in the list. This is useful for faceted views, or other cases where the ordering is unimportant. For dead end lists, there is a definitive start and stop, and (aside from links such as "back to top") there is no way to go to the other end. These are useful for information with a very ordered, single-axis display. Most hierarchies, and much date-sorted information should display like this. Such as a message list that starts with the most recent. For clarity, above the most recent message is nothing (or controls to make a new message), not the oldest message. Very often, the manner of the data must be combined with the appropriateness of a solution to select the pattern. '''[[Carousel|Carousels]]''', for example, work best when circular, and '''[[Grid|Grids]]''' work well as dead ends. Additional details of list navigation are detailed under the appropriate Widget section. |

Date and location are essentially special cases, and depending on the data or needs they may be approached either way, even though they are strictly defined. For example, location can be an arbitrary value, with filtering or sorting for distance around a single point. Or it may be considered as a hierarchy of continent → nation → state → county → city → address. |

| Line 65: | Line 105: |

| === Developing an Information Architecture === Actually developing the information architecture of the product, service or even a single display is a lengthy process, outside the scope of this book. Among other things, it very often will have to work within technical constraints, or legacy (even third-party) data repositories or business practices. |

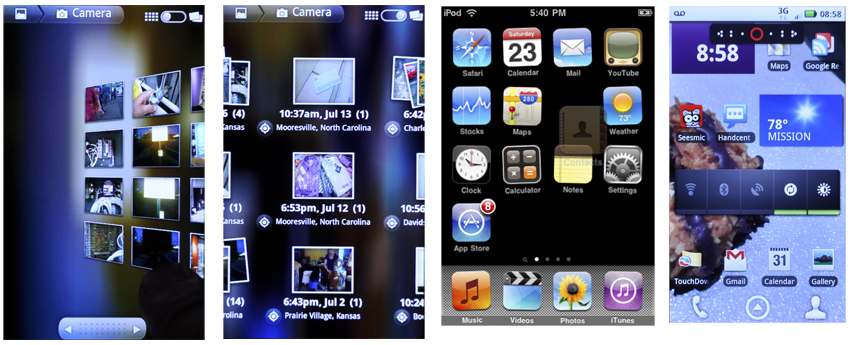

== Information Design and Ordering Data == [[http://www.flickr.com/photos/shoobe01/6501514531/|{{attachment:DisplayInfoIntro-Grid.png|Figure 2-2. Grids are used to display ordered data such as photos by date, or for user-organized information such as home pages, where they often become filmstrips as well. Grids can lend themselves to selection, reorganization, and even inclusion of larger items, as long as they fit in the grid.}}]] |

| Line 68: | Line 108: |

| If you have a chance to perform user research, and develop a model informed by the principles above, and actual needs then by all means do so. What you are seeking from this is the true needs and expectations of users. Note, there are three types of knowledge that the users have in their head, and a lot of the methods you may encounter (e.g. focus groups) at best only gather from one of these segments. All have to be considered. | You can use the way in which people perceive attributes to communicate the relative im- portance and relationship of informational elements on the page. This design of pages or states, when it falls directly from the information architecture of the entire product, can be called information design. Although many methods of considering these arrangements exist, an adequate grouping is from most to least important. Position is generally more critical to communicating im- portance than size, which is more important than shape, and so on: |

| Line 70: | Line 111: |

| ==== Explicit ==== Explicit knowledge can be easily described. It is knowledge that can be written down, spoken, and shared. Naming all 50 US states, writing down the lyrics of your favorite song, or explaining how to use Google Maps are all examples of explicit knowledge. This sort of knowledge is easily accessed and is on the highest cognitive level. This is knowledge that describes current and past experiences, but lacks a connection to future experiences like dreams, aspirations, and fears. Some methods you can use to access people's explicit knowledge are: * Interviews. * Storytelling. * Explaining directions or procedures. * Documenting in a journal, with photos, or other methods. |

''Position'' Although relative position is unarguably critical, it can easily be lost. The [[Annunciator Row]], with battery level and so forth, is not the most important, because it is almost lost in the bezel. This is purposeful, and the size is adjusted to account for it. Each attribute works with others to function properly. |

| Line 77: | Line 114: |

| ==== Observable Knowledge ==== Observable knowledge can be shown by action and procedure. Drawing a map of all 50 states, putting together a jigsaw puzzle or playing a favorite song are examples of observable knowledge. This level of knowledge is easily accessed, and is stored at a deeper cognitive level. This knowledge will describe current and past experiences, but lacks a connection to future experiences like dreams, aspirations, and fears. Some methods you can use to access people's observable knowledge are listed below. * Mental model drawings. * Acting out behaviors. * Using objects, or services, in context. |

''Size'' Larger elements attract more attention, aside from providing more room for content. They can be too big, either obscuring other items or exceeding the expectation size for an element. Buttons can be so large that they are not recognized as buttons, for example. |

| Line 83: | Line 117: |

| ==== Tacit Knowledge ==== Tacit knowledge is not easily shared or written down. It is the knowledge of discovery and creation. It stems from our desire to know more, to create something new, original, playful, challenging, and satisfying. Tacit knowledge is deeply embedded within our cognition. Examples of tacit knowledge are creating an abstract painting, sculpting pieces of clay into a vase, navigating yourself through an unknown city, and swimming the freestyle. The following methods can be used to generate tacit knowledge: * Collaging * Co-Discovery * Model Making |

''Shape'' At their simplest, pointed shapes attract attention. Warnings should be triangles, and helpful icons circles, for example. Rounded corners on some boxes, and square on others, will imply meaning. Make sure it’s there, and not just a random design element. |

| Line 89: | Line 120: |

| User's behaviors and beliefs can be quite different from each others, and from your point of view, from the inside of a system. To understand why, we needed to understand that our experiences and perceptions are embedded within different knowledge levels. These knowledge levels can be easily and quickly recalled, or deeply embedded and latent, where methods of discovery and creation are needed to access them. | ''Contrast'' Contrast refers not to color, but the comparative value (darkness) between two dif- ferent elements, discounting color. Contrasting elements are more easily read, less affected by lighting conditions, and not as subject to users with color deficit. |

| Line 91: | Line 123: |

| Once you have gathered and analyzed information like this, you can use generate user needs, rank them in importance, and group them into categories. This will rapidly become a usable information architecture. Conflicts with technical systems are usually smaller than you'd expect, and can easily be mitigated by carefully comparing the ideal, user-centered diagrams and the true technical requirements. | ''Color'' High-visibility colors attract more attention, with significant caveats. The most important caveat is not always regarding colorblind users. Glare can make certain colors less prominent. Pervasive use of the color in the branding can also be problematic; a site with a lot of red cannot rely on red for warnings. |

| Line 93: | Line 126: |

| ''Form'' The last thing to use is specific forms of an element. The most common is type treat- ments, such as bold and italics. |

|

| Line 94: | Line 129: |

| == Visual Perception == After our senses collect visual information, our brain begins to perceive and store the information. Perception involves taking information that was delivered from our senses and interacting it with our prior knowledge stored in memory. This process allows us to relate new experiences with old experiences. During this process of visualization of perception, our minds look to identify familiar patterns. Recognizing patterns is the essential for object perception. Once we have identified an object, it is much easier to identify the same object on a subsequent appearance anywhere in the visual field (Biederman and Cooper, 1992). |

We will discuss these in detail in other chapters as well. Here, the concept is useful when determining how to relate the elements within a single informational item, and how to keep the elements and adjacent items from becoming mixed. Rules and bars of color are but some of the techniques. The preceding list covers six categories, with hundreds of design tactics included. |

| Line 97: | Line 131: |

| The Gestalt School of Psychology was founded in 1912 to study how humans perceive form. The Gestalt principles they developed can help designers create visual displays based on the way our minds perceive objects. These principles, as they apply to mobile interactive design are: | It is also useful to decide what information must be present. More can be said about a good, easy-to-understand interactive design by what is left out of any particular view, than what is included. For each of the information displays detailed in this section, only a portion is shown, and details, or alternative views, are available when the user takes action. |

| Line 99: | Line 133: |

| * '''Proximity''' - Objects that are close together are perceived as being related and grouped together. When designing graphical displays, having descriptive text close to an image will cause the viewer to relate the two objects together. This can be very effective when dual coding graphical icons. * '''Similarity''' - Objects sharing attributes are perceived to be related, and will be grouped by the user. Navigation tabs that are similar in size, shape, and color, will be perceived as a related group by the viewer. * '''Continuity''' Smooth, continuous objects imply they are connected. When designing links with nodes or arrows pointing to another object, viewers will have an easier time establishing a connected relationship if the lines are smooth and continuous and less jagged. * '''Symmetry''' - Symmetrical relationships between objects imply relationships. Objects that are reflected symmetrically across an axis, are perceived as forming a visual whole. This can be bad more easily than good. If a visual design grid is too strict, unrelated items may be perceived as related, adding confusion. * '''Closure''' - A closed entity is perceived as an object. We have a tendency to close contours that have gaps in them. We also perceive closed contours as having two distinct portions: an inside and outside. When designing list patterns, like the grid pattern described in this chapter, use closure principles to contain either an image or label. * '''Relative Size''' - Smaller components within a pattern are perceived as objects. When designing lists, using entities like bullets, arrows, nodes inside a group of information, will be viewed as individual objects that our eyes will be drawn to. Therefore, make sure these objects are relevant to the information that it is relating to. Another example of relative size is a pie with a missing piece. The missing piece will stand out and be perceived as an object. * '''Figure and Ground''' - A figure is an object that appears to be in the foreground. The ground is the space or shape that lies behind the figure. When an object uses multiple gestalt principles, figure and ground occurs. Now that we have an understanding that visual object perception is based on identifying patterns, we must be able to design visual displays that mimic the way our mind perceives information. Stephen Kossyln states “We cannot exploit multimedia technology to manage information overload unless we know how to use it properly. Visual displays must be articulate graphics to succeed. Like effective speeches, they must transmit clear, compelling, and memorable messages, but in the infinitely rich language of our visual sense” (Kossyln, 1990). In his article, Kossyln identifies and describes five key principles for articulate graphics: === Display Elements are Organized Automatically === This follows gestalt principles. Objects that are close by, collinear, or look similar tend to be perceived as groups. So when designing information displays, like maps, adding indicators, landmarks, and objects that are clustered together, appear to be grouped and share a relationship. This may cause confusion when the viewer needs to locate his exact position. === Perceptual Organization is Influenced by Knowledge === When looking at objects in a pattern for the first time, the organization may not be fully understood or remembered. However, if this pattern is seen again over time, we tend to chunk this pattern and store it in our memory. Think of chessboard with its pieces played out. To a viewer who has never seen this game before, will perceive the board as having many objects. However, an experienced chess player, will immediately identify the objects and the relationships that have with each other and the board. So when designing visual displays, its essential to know the mental model of your user so they may quickly identify and relate to the information displayed. === Images are transformed Incrementally === When we see an object move and transform its shape in incremental steps, we have an easier time understanding that the two objects are related or identical. However, if we only see the object’s beginning state and end state, our minds are forced to use a lot of mental processing and load to understand the transformation. This can take much more time and also increase errors or confusion. So when designing carousel lists, make sure the viewer can see the incremental movement. === Different Visual Dimensions are Processed by Separate Channels === Object attributes such as color, size, shape, and position are processed with our minds using separate processing channels. The brain processes many individual visual dimensions in parallel at once, but can only deal with multiple dimensions in sequence. For example, when designing bullet list that are all black circles, we can immediate identify all of them. However, if you add a bullet that is black, same size, but diamond shape, our minds have to work harder to perceive them as being different. ==== Color is Not Perceived as a Continuum ==== Many times designers will use color scale to represent a range of temperature, like red is hot. Blue is cold. And temperatures in between will be represented by the visual spectrum. The problem is that our brains do not perceive color this way in a linear dimension. We view color based on the intensity and amount of light. So a better way of showing this temperature difference would be to use varying intensity and saturation. == Information Design & Ordering Data == The way people perceive attributes can be used directly to communicate the relative importance and relationship of informational elements on the page. This design of pages or states, when it falls directly from the information architecture of the entire product, can be called information design. While many methods of considering these arrangements exist, an adequate grouping is, from most to least important. Position is, generally, more critical to communicating importance than size, which is more important than shape, and so on: * '''Position''' - While relative position is unarguably critical, it can easily be lost. The annunciator row, with battery level and so forth, is not the most important, because it is almost lost in the bezel. This is purposeful, and the size is adjusted to account for it. Each attribute works with others to function properly. * '''Size''' - Larger elements attract more attention, aside from providing more room for content. They can be too big, either obscuring other items, or exceeding the expectation size for an element. Buttons can be so large they are not recognized as buttons, for example. * '''Shape''' - At the simplest, pointed shapes attract attention. Warnings should be triangles, helpful icons circles, for example. Rounded corners on some boxes, and square on others, will imply meaning. Make sure it's there, and not just a random design element. * '''Contrast''' - Not color, but the comparative value (darkness) between two different elements, discounting color. More easily read, less affected by lighting conditions, and not as subject to users with [[Color Deficit Design Tools|color deficits]]. * '''Color''' - High visibility colors attract more attention, with significant caveats. The most important is not always color blind users. Glare can make certain colors less prominent. Or pervasive use of the color in the branding; a site with much red cannot rely on it for warnings. * '''Form''' - The last thing to use is specific forms of an element. The most common is type treatments, such as bold and italics. These will be discussed in detail in other chapters as well. Here, the concept is useful when determining how to relate the elements within a single informational item, and how to keep the elements adjacent items from becoming mixed. Rules and bars of color are but some of the techniques. The list above covers six categories, with hundreds of design tactics included. It is also useful to decide what information must be present. More can be said about a good, easy to understand interactive design by what is left out of any particular view, than what is included. For each of the information displays detailed below, only a portion is shown, and details, or alternative views are available when the user takes action. Naturally, make these decisions by following heuristics, standards, styles of design that already exist such as OS-level standards, and universal hierarchies of visual communication. Most decisions for an existing platform can be made easier by consulting the style guide. Only a few choices will exist, and these will be well understood by the users. |

Naturally, make these decisions by following heuristics, standards, and styles of design that already exist, such as OS-level standards and universal hierarchies of visual communication. Most decisions for an existing platform can be easier to make by consulting the style guide. Only a few choices will exist, and these will be well understood by users. |

| Line 147: | Line 137: |

| A valid way of thinking about the entire topic of interactive design is that it is about displaying information. This chapter in particular is concerned with components whose sole task is presenting ordered sets of information, so that users may understand and act upon them. | One good way to think about the topic of interactive design is that it’s all about displaying information. This chapter in particular is concerned with components whose sole task is to present ordered sets of information so that users may understand and act upon them. |

| Line 150: | Line 140: |

| * [[Vertical List]] * [[Infinite List]] * [[Thumbnail List]] * [[Fisheye List]] * [[Grid]] * [[Film Strip]] * [[Slideshow]] * [[Infinite Area]] * [[Select List]] |

''[[Vertical List]]'' Rather than using horizontal space inefficiently, this displays a set of information vertically using an entire allocated space. See Figure 2-1. ''[[Infinite List]]'' This reveals small amounts of vertical information at a time because the information set is very large, and not locally stored. ''[[Thumbnail List]]'' This uses a [[Vertical List]] with additional graphical information to assist in the user’s understanding of items within the data set. ''[[Fisheye List]]'' When a scroll-and-select device is targeted, and a Vertical List is called for, this can be used to reveal small amounts of additional information that can assist the user in his task. ''[[Carousel]]'' This displays a set of selectable images, not all of which can fit in the available space but which can be scrolled through using many methods. Preserve the integrity of the image used. Do not use programmatic shortcuts visible to the user: * If the image is skewed to create perspective, skew the entire image. Don’t clip off corners of the image to simulate the skew, as demonstrated in Figure 2-10. * Do not squash the image to change its aspect ratio. If necessary, add black bars or crop the image to fit a consistent space. * Do not flip the image when displaying the back of a card, as in three-dimensional carousels. Never use cheats, and come up with a different display method, or switch to another pattern such as a [[Grid]] or [[Slideshow]]. ''[[Grid]]'' This presents information as a set of tiles, most or all of which are unique images, for selection. See Figure 2-2. ''[[Film Strip]]'' This presents a set of information, which either is a series of screen-size items or can be grouped into screens, for viewing and selection. ''[[Slideshow]]'' This presents a set of images or similar pieces of information using the full screen for viewing and selection. ''[[Infinite Area]]'' This displays large, complex, and/or interactive visual information which must be routinely zoomed in on so that only a portion is visible in the viewport. ''[[Select List]]'' This is usually a mode of another list pattern when selections, either individual or multiple, must be made from a large, ordered data set. ------- = Discuss & Add = Please do not change content above this line, as it's a perfect match with the printed book. Everything else you want to add goes down here. == Examples == If you want to add examples (and we occasionally do also) add them here. == Make a new section == Just like this. If, for example, you want to argue about the differences between, say, Tidwell's Vertical Stack, and our general concept of the List, then add a section to discuss. If we're successful, we'll get to make a new edition and will take all these discussions into account. |

Look Around

Take a moment and look around. Are you inside? Then you might come across books, a pile of mail, your computer, and your television. Or maybe you’re outside, carrying your mobile device and checking your appointments. The world we live in is surrounded by ubiquitous information. Information that is visual, audible, and tactile. It is meant to inform, to entertain, to instruct, and to warn. Because we are constantly bombarded with this information in our daily lives, we must quickly collect, filter, store, and process which information is important to use for specific tasks.

Consider a busy intersection you are trying to cross. You are surrounded by the sights and sounds of pedestrians conversing, cars and trucks honking, birds flying, signage on billboards, and thousands of other types of stimuli. Our minds have an amazing ability to focus on the task at hand, filter the surrounding noise, and process, store, and allow us to act on only the relevant “signal” information.

When the crosswalk signal changes to “Walk,” we identify the sign, interpret its meaning, determine an action to move our body forward, and carry out our actions by walking until we’ve crossed the street, achieving our goal.

Understanding how we process and filter visual information, or data, will help us to design effective displays of information on mobile devices. Let’s first explore the types of information we will encounter.

Types of Visual Information

All humans have more or less the same visual processing system. However, without a standardized way to explain and notate our perceptions, our communication of this in- formation becomes arbitrary and ineffective when designing to display information on mobile interfaces.

Ware (Ware 2000) introduces a modern way of dividing data into entities and relationships.

Entities are the objects that can be visualized, such as people, buildings, and signs. Relationships (sometimes called relations) define the structures and patterns that entities share with one another. Relationships can be structural and physical, conceptual, causal, and temporal.

These entities and relationships can be further described using attributes. These are properties of both the entity and the relationship, and cannot be considered independently. Some examples of attributes are:

- Color

- Duration

- Texture

- Weight, or thickness of a line

- Type size

For each of these we mean the attribute as it applies to a specific item. Not texture in general, or the texture of paper, but the texture of a specific type of paper (or even a specific sheet of paper).

Classifying Information

In addition to creating descriptions of our perceptions, we have also standardized a way to classify them. Common classifying schemes that we use are:

Nominal

- Uses labels and names to categorize data

Ordinal

- Uses numbers to order things in sequence

Ratio

- A fixed relationship between one object and another using a zero value as a reference

Interval

- The measurable gap between two data values

Alphabetical

- Uses the order of the alphabet to organize nominal data

Geographical - Using location, such as city, state, country, to organize data.

- Uses location, such as city, state, and/or country, to organize data

Topical - Organizing data by topic or subject.

- Organizes data by topic or subject

Task - Organizing data based on processes, tasks, functions and goals.

- Organizes data based on processes, tasks, functions, and goals

Audience - Organizing data by user type, such as interests, demographics, knowledge and experience levels, needs and goals.

- Organizes data by user type, such as interests, demographics, knowledge and experi- ence levels, needs, and goals

Social - A collaboration of organizing data by users who share the same interests. Such as tagging, adding to a wiki, and creating and following twitter feeds.

- A collaboration of organizing data by users who share the same interests, such as tag- ging, adding to a wiki, and creating and following Twitter feeds

Metaphor - Organizing data based on a familiar mental model to the user. Such as organizing computer files with folders, trash, and recycle bin.

- Organizes data based on a mental model that is familiar to the user, such as organiz- ing computer files with folders, trash, and a recycle bin

Organizing with Information Architecture

Now that we can describe the data we perceive and knowledge types we store, we must understand how this information should be structured, organized, labeled, and identified on mobile user interfaces.

Now that we can describe the data we perceive and knowledge types we store, we must understand how this information should be structured, organized, labeled, and identified on mobile user interfaces.

One of the most common organization structures humans have used through time is a hierarchy. A hierarchy organizes information based on divisions and parent-child relationships. When using hierarchies to organize information, Peter Morville explains rules to consider (Morville 2006): categories should be mutually exclusive to limit ambiguity. Consider the balance between breadth and depth. When determining the number of cat- egories regarding breadth, you must consider the user’s ability to visually scan the page as well as the amount of real estate on the screen. When considering depth, limit the scope to two to three levels down. Recognize the danger of providing users with too many options.

Another way to organize information is by faceting. In this, there are no parent-child relationships, just information attributes, such as tags, which may be sorted or filtered to display the most appropriate information. The tags do not have to be explicit, and faceting may be accomplished by searching text descriptions, or even through unusual methods such as searching for shapes, patterns, or colors directly within images.

Of course, these two methods, hierarchy and faceting, may be used in conjunction. A hierarchically ordered data set can also have tags attached to it, and the facet view may combine both strict and arbitrary ordering to display the information the user wants.

Date and location are essentially special cases, and depending on the data or needs they may be approached either way, even though they are strictly defined. For example, location can be an arbitrary value, with filtering or sorting for distance around a single point. Or it may be considered as a hierarchy of continent → nation → state → county → city → address.

Information Design and Ordering Data

You can use the way in which people perceive attributes to communicate the relative im- portance and relationship of informational elements on the page. This design of pages or states, when it falls directly from the information architecture of the entire product, can be called information design. Although many methods of considering these arrangements exist, an adequate grouping is from most to least important. Position is generally more critical to communicating im- portance than size, which is more important than shape, and so on:

Position

Although relative position is unarguably critical, it can easily be lost. The Annunciator Row, with battery level and so forth, is not the most important, because it is almost lost in the bezel. This is purposeful, and the size is adjusted to account for it. Each attribute works with others to function properly.

Size

- Larger elements attract more attention, aside from providing more room for content. They can be too big, either obscuring other items or exceeding the expectation size for an element. Buttons can be so large that they are not recognized as buttons, for example.

Shape

- At their simplest, pointed shapes attract attention. Warnings should be triangles, and helpful icons circles, for example. Rounded corners on some boxes, and square on others, will imply meaning. Make sure it’s there, and not just a random design element.

Contrast

- Contrast refers not to color, but the comparative value (darkness) between two dif- ferent elements, discounting color. Contrasting elements are more easily read, less affected by lighting conditions, and not as subject to users with color deficit.

Color

- High-visibility colors attract more attention, with significant caveats. The most important caveat is not always regarding colorblind users. Glare can make certain colors less prominent. Pervasive use of the color in the branding can also be problematic; a site with a lot of red cannot rely on red for warnings.

Form

- The last thing to use is specific forms of an element. The most common is type treat- ments, such as bold and italics.

We will discuss these in detail in other chapters as well. Here, the concept is useful when determining how to relate the elements within a single informational item, and how to keep the elements and adjacent items from becoming mixed. Rules and bars of color are but some of the techniques. The preceding list covers six categories, with hundreds of design tactics included.

It is also useful to decide what information must be present. More can be said about a good, easy-to-understand interactive design by what is left out of any particular view, than what is included. For each of the information displays detailed in this section, only a portion is shown, and details, or alternative views, are available when the user takes action.

Naturally, make these decisions by following heuristics, standards, and styles of design that already exist, such as OS-level standards and universal hierarchies of visual communication. Most decisions for an existing platform can be easier to make by consulting the style guide. Only a few choices will exist, and these will be well understood by users.

Patterns for Displaying Information

One good way to think about the topic of interactive design is that it’s all about displaying information. This chapter in particular is concerned with components whose sole task is to present ordered sets of information so that users may understand and act upon them.

These patterns have been developed and refined based on how the human mind processes patterns, objects, and information:

- Rather than using horizontal space inefficiently, this displays a set of information vertically using an entire allocated space. See Figure 2-1.

- This reveals small amounts of vertical information at a time because the information set is very large, and not locally stored.

This uses a Vertical List with additional graphical information to assist in the user’s understanding of items within the data set.

- When a scroll-and-select device is targeted, and a Vertical List is called for, this can be used to reveal small amounts of additional information that can assist the user in his task.

- This displays a set of selectable images, not all of which can fit in the available space but which can be scrolled through using many methods. Preserve the integrity of the image used. Do not use programmatic shortcuts visible to the user:

- If the image is skewed to create perspective, skew the entire image. Don’t clip off corners of the image to simulate the skew, as demonstrated in Figure 2-10.

- Do not squash the image to change its aspect ratio. If necessary, add black bars or crop the image to fit a consistent space.

- Do not flip the image when displaying the back of a card, as in three-dimensional carousels.

Never use cheats, and come up with a different display method, or switch to another pattern such as a Grid or Slideshow.

- This presents information as a set of tiles, most or all of which are unique images, for selection. See Figure 2-2.

- This presents a set of information, which either is a series of screen-size items or can be grouped into screens, for viewing and selection.

- This presents a set of images or similar pieces of information using the full screen for viewing and selection.

- This displays large, complex, and/or interactive visual information which must be routinely zoomed in on so that only a portion is visible in the viewport.

- This is usually a mode of another list pattern when selections, either individual or multiple, must be made from a large, ordered data set.

Discuss & Add

Please do not change content above this line, as it's a perfect match with the printed book. Everything else you want to add goes down here.

Examples

If you want to add examples (and we occasionally do also) add them here.

Make a new section

Just like this. If, for example, you want to argue about the differences between, say, Tidwell's Vertical Stack, and our general concept of the List, then add a section to discuss. If we're successful, we'll get to make a new edition and will take all these discussions into account.