Problem

Lateral access must be provided to a small number of items at the same level in the information architecture, while also clearly communicating this hierarchy of information.

Solution

Tabs are based on real life objects, the tab labels that stick up from file folders. The folders contain information that takes up too much room to just leave on the desk. To make sure they work, follow the same principles as the paper and file cabinet:

- Clearly label what is inside them.

- Indicate when you have the one you want selected, or open.

- Make sure all tabs and labels are visible at once, or it is clear there are more to be seen if you try harder.

Tabs do not actually have to look like file folder tabs, with rounded corners, or even with any container at all. But the principles still apply. For interactive applications, one (and only one) tab is always opened, and the contents are visible.

Tabs are generally only used for sets of pages or features between three and eight items. When using with only two items, the design may fall apart, and must be carefully designed to make it clear which is selected. Larger sets, especially when they do not all fit on the page, may cause the user to become lost. If very large lists of items within the information architecture must be displayed, consider a more list-list pattern instead, or re-consider if the IA is correctly built.

Variations

Aside from graphic design distinctions, there are basically two axes upon which tabs may vary:

Tabs may be used across the site, application or process, as an indicator and access point to the highest level of navigation available without exiting. Or, they may be used within a single page or page template to provide access between broadly equivalent types of information without logically leaving the page.

All the available tabs should whenever possible, be visible at all times. However, this is often not possible due to labels being too large for the screen. Tabs which do not fit may fall off the sides of the screen, and those that fit will appear as focus shifts. In the most extreme case, only a single tab will fit the screen, and sideways scrolling is required to see any other tabs.

Interaction Details

For scroll and select devices, tabs are most useful when the remaining content only requires vertical scrolling. In this case, pressing the Left or Right scroll keys anywhere on the page will switch focus to the current item in the tab bar, and subsequent presses will switch focus to the next item in line. Pressing OK/Enter will select the tab and switch to that page, section or function.

When using a tab bar to switch out content for a subsection of a page, sideways scrolling among those tabs will become available when vertical scrolling has brought the tab bar into focus. The current item will be in focus, and others may be focused in the usual manner. While in this tab row, any other tab rows may not be accessed.

Tab rows should always be circular lists. When at the end of the list, another directional press in the end-of-list direction will jump to the front of the list.

Touch and pen will directly interact with tabs. However, this can be a problem as the tabs must be correspondingly larger to allow for the touch target. Again, unless the labels can be small enough or the device is large, tabs may not be the best option. For cases where not all tabs fit on the screen, scrolling (by dragging) may allow browsing of the whole tab row.

For any selection mechanism, selecting a tab when the tab row does not entirely fit on the screen will cause the tab to become centered immediately. If not technically possible, it will assume the centered position when the new content loads.

Presentation Details

Tabs really only work well when arrayed horizontally, or when all are on one row. Vertical tabs of any sort are rarely are understood by the user to be tabs, so will not be discussed here.

The highlighted tab may be used as a label for the page or component. Assure that it is clear, readable and sufficiently prominent to serve both roles.

Tab labels are generally text. Icons may be used to support them, but will rarely be understood sufficiently without text. Use labels in a consistent manner, and assure they are clear and jargon-free. See the Titles pattern for more discussion of labeling.

Tab rows should be presented as though they are dead end lists, with fixed end points. Only when an overflow action is selected will the user jump to the extreme other tab. Animation may be used for tab rows that do not fit on the screen -- rapidly scrolling back to the other end of the list -- to more clearly communicate this.

When not all tabs fit on the screen, an indication that there are more must be made. There are three basic methods:

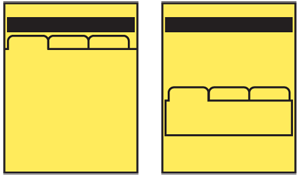

- Fit whatever is possible, so parts of tab containers and labels are on the screen. This is most clear, but can be perceived as "messy" by some interface designers"

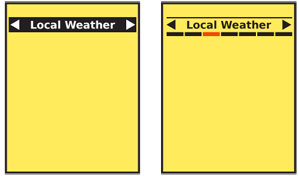

- Only fit complete tab labels on the screen, including as few as one tab. The presence of additional items is only communicated with an indicator (such as an arrow) at the ends of the list with additional items. This can be more difficult to discover so should be designed carefully to assure the indicators are clear and visible.

- Use "magnification" to indicate the position in the complete list in a tab-like manner, while providing a much smaller number of labels at a a readable size.

Any indicators that there are more tabs off the screen must reflect actual content with the dead-end list paradigm; when the end of the list is reached, stubbed tab containers, arrows, and other indicators there is more content must be removed.

When scrolling through the tab list, make sure a visible but non-selected tab is different from the selected one, even without comparison, so that users do not mistake it for the page Title.

Antipatterns

When only one or a few tabs are visible, assure the tab paradigm is clear, and it is obvious the tab is not just a page title, but is one option of many to be chosen from.

Clever solutions for space rarely work, so follow best practices and existing working methods before attempting to develop your own solutions. A second row of tabs always is perceived as subsidiary to the top row, and is not read as a second row of text would be.

Avoid using tabs for both high-level and in-page navigation. If needed, differentiate the two in some key way to express the hierarchical difference.

When tabs are used within a page (such as providing a switch between overview, detailed specifications, and reviews), avoid refreshing the entire page. Logically, and by convention that users are familiar with now, this should only load the requested information, and leave the rest in place, without even flickering.

When scroll-and-select is the only selection mechanism, and page interaction is two dimensional, or uses a virtual cursor, tabs are not suggested as they may be slow and difficult to select.

Do not use conventional circular list presentation, where the last tab is adjacent to the first tab. Users will loose track of their position in the list.

Avoid using Pagination ("1 of 6") or other generalized Location Within widgets to indicate how many tabs are available. These patterns are associated with other access methods, so may disrupt building an accurate mental model of the IA.