The varying ways people prefer to interact with their devices is highly dependent upon their natural tendencies, comfort levels, and the context of use. As designers and developers, we need to understand these influences and offer user interfaces that appeal to these needs.

User preferences may range from inputting data using physical keys, natural handwriting, or other gestural behaviors. Some users may prefer to receive information with an eyes-off screen approach relying on haptics or audible notifications.

This section, Input & Output, will discuss in detail the different mobile methods and controls users can interact with to access and receive information.

The types of input and output that will be discussed here are subdivided into the following chapters:

Chapter 10, Text & Character Input

Chapter 11, General Interactive Controls

Chapter 12, Input & Selection

Chapter 13, Audio & Vibration

Chapter 14, Screens, Lights & Sensors

Types of Input & Output

Text & Character Input

Whether the reason is sending an email, SMS, searching, or filling out forms, users require ways to input both text and characters. Such methods may be through keyboards and keypads, by hardware keys, touch screens and pen-based writing. Regardless of the method, they must each allow rapid input, while reducing input errors and providing methods of correction. This chapter will explain research based frameworks, tactical examples, and descriptive mobile patterns to use for text and character input.

This chapter will discuss the following patterns:

General Interactive Controls

Functions on the device, and in the interface, are influenced by a series of controls. They may be keys arrayed around the periphery of the device, or be controlled by gestural behaviors. Users must be able to find, understand, and easily learn these control types. This chapter will explain research based frameworks, tactical examples, and descriptive mobile patterns to use for general interactive controls.

This chapter will discuss the following patterns:

Input & Selection

Users require methods to enter and remove text and other character-based information without restriction. Many times users are filling out forms or selecting information from lists. At any time, they may also need to make quick, easy changes to remove contents from these fields or entire forms. This chapter will explain research based frameworks, tactical examples, and descriptive mobile patterns to use for input and selection.

This chapter will discuss the following patterns:

Audio & Vibration

Our mobile devices are not always in plain sight. They may across the room, or placed deep in our pockets. When important notifications occur, users need to be alerted. Using audio and vibration as notifiers and forms of feedback can be very effective. This chapter will explain research based frameworks, tactical examples, and descriptive mobile patterns to use for audio and vibration.

This chapter will discuss the following patterns:

Screens, Lights & Sensors

Mobile devices today are equipped with a range of technologies meant to improve our interactive experiences. These devices may be equipped with advanced display technology to improve viewability while offering better battery life, and incorporate location base services integrated within other applications. This chapter will explain research based frameworks, tactical examples, and descriptive mobile patterns to use for screens, lights, and sensors.

This chapter will discuss the following patterns:

Helpful knowledge for this section

Before you dive right into each pattern chapter, we like to provide you some extra knowledge in the section introductions. This extra knowledge is in multi-disciplinary areas of human factors, engineering, psychology, art, or whatever else we feel relevant.

This section will provide background knowledge for you in the following areas:

- General Interactive Touch Guidelines.

- Understanding Brightness, Luminance, and Contrast.

- How our hearing works.

General Touch Interaction Guidelines

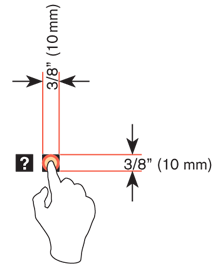

The minimum area for touch activation, to address the general population, is a square 3/8” on each side (10 mm). When possible, use larger target areas. Important targets should be larger than others.

There is no distinct preference for vertical or horizontal finger touch areas. All touch can be assumed to be a circle, though the actual input item may be shaped as needed to fit the space, or express a preconceived notion (e.g. button). Due to reduced precision and poor control of pressure, but smaller fingers, children who can use devices un-assisted have the same touch target size.

Targets

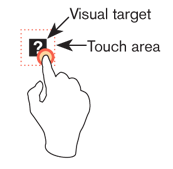

The visual target is not always the same as the touch area. However the touch area may never be smaller than the visual target. When practical (i.e. there is no adjacent interctive item) the touch area should be notably larger than the visual target, filling the "gutter" or white-space between objects. Some dead space should often be provided so edge contact does not result in improper input.

In the example, the orange dotted line is the touch area. It is notably larger than the visual target, so a missed touch (as shown) still functions as expected.

Touch area and the centroid of contact

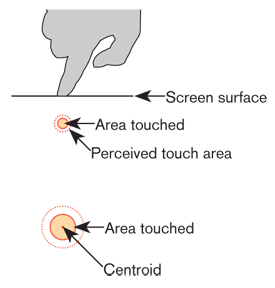

The point activated by a touch (on capacitive touch devices) is the centroid of the touched area; that area where the user’s finger is flat against the screen.

The centroid is the center of area whose coordinates are the average (arithmetic mean) of the co-ordinates of all the points of the shape. This may be sensed directly (the highest change in local capacitance for projected-capacitive screens) or calculated (center of the obscured area for beam-sensors).

A larger area will typically be perceived to be touched by the user, due to parallax (advanced users may become aware of the centroid phenomenon, and expect this).

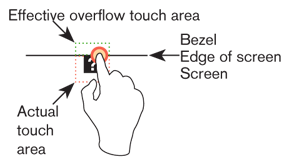

Bezels, edges and size cheats

Buttons at the edges of screens with flat bezels may take advantage of this to use smaller target sizes. The user may place their finger so that part of the touch is on the bezel (off the sensing area of the screen). This will effectively reduce the size of their finger, and allow smaller input areas.

This effective size reduction can only be about 60% of normal (so no smaller than 0.225 in or 6 mm) and only in the dimension with the edge condition. This is practically most useful to give high priority items a large target size without increasing the apparent or on-screen size of the target or touch area.

Brightness, Luminance, and Contrast

These terms are confusing to almost everyone, largely as a result of hardware manufacturers mislabeling display controls since the dawn of television. Apparently, this was to make it easier on the general public, but the result is an improper mental model, making it hard to adjust or design for electronic displays properly.

Brightness

Brightness refers to our subjective perception of how bright an object is. Therefore, what may seem very bright to you, may be less bright to me. We can use subjective words such as dim and very bright to describe our perceptions of brightness.

When mobile device displays provide controls to adjust screen brightness, it’s really controlling the amount of light emitted from the device. But when we are controlling the amount of light on a display, we’re really concerned with how bright it feels to us, and how comfortable we are at that level of luminance.

Luminance

Luminance is the measure of light an object gives off or reflects from its surface. Luminance is measured in different units such as candela (cd/m2), footlambert (ftL), mililambert (mL), and Nit (nt).

When a brightness control is available, the actual function being controlled is the display luminance, either via control of backlight brightness for LCDs, or of the "white point" setting for LEDs. Since luminance values are not commonly encountered, some example figures may be usefully illustrative:

A typical computer display emits between 50 and 300 cd/m2.

Some mobile devices are now capable emitting up to 300 cd/m2 of luminance.

Riggs (1971) notes that in starlight (luminance of .0003 cd/m2) we can see the white pages of a book but not the writing on them.

The recommended luminance standard for measuring acuity is 85 cd/m2 (Olzak and Thomas, 1996).

- For text contrast, the International Standards Organization (ISO 9241, part 3) recommends a minimum of 3:1 luminance ratio of text and background. Though a ratio of 10:1 is preferred (Ware, 2000).

Remember that luminance and brightness are not measured in the same manner. For example, if you lay out a piece of black paper in full sunlight on a bright day, you may measure a value of 1000 cd/m2. If you view a white piece of paper in an office light, you will probably measure a value of only 50 cd/m2. Thus, a black object on a bright day outside may reflect 20 times more light than white paper in the office (Ware, 2000).

Contrast

Contrast is the difference in visual properties that makes an object stand apart from other objects or background. Generally, this is the difference between the perceived brightness values of the highest white level compared to the darkest black level. High ambient light levels can reduce the perceived (or, depending on the display technology, actual) contrast.

Functional contrast can be strongly influenced by the designer. If multiple gray tones are used adjacent to each other, they may be perceived easily under ideal conditions, but blend together in poor conditions.

Black Level

Contrast is to black level as brightness is to luminance. Generally, contrast control is performed by adjusting the black level, or the amount of light emitted or transmitted by the low end of the display output.

Note that these controls work differently on other display types, like CRTs. Some display types (most ePapers) have no meaningful control over contrast (or black level) at all.

How Our Hearing Works

Our sense of hearing plays a critical role in our ability to perform daily activities. Before our ears can detect sound, acoustic energy begins in the form of sound waves traveling through the air. These sound waves strike our eardrum, which sends them into our inner ear. Inside the inner ear are nerve impulses that are then transmitted to and perceived by the brain.

Measuring Sound

Sound waves are measured in two ways. In both frequency and intensity:

Frequency is the number of cycles of pressure change occurring in one second and is measure in hertz (Hz). We perceive frequency as pitch. Humans can hear sound wave frequencies ranging from 20 to 20,000 Hz. When designing for the general population, expect them to detect frequencies from 1,000 to 4,000 Hz.

Intensity is determined by the amount of pressure a sound wave strikes the eardrum and is measure in decibels (dB). We perceive intensity as loudness. Frequency ranges from 1000 to 8000 Hz require the least intensity to be heard. And tones at lower frequencies must have larger intensities to be heard. As people age, their ability to hear higher frequencies is greatly reduced. By the time most people reach 65, very few can still detect frequencies over 10,000 Hz.

Decibels are a logarithmic measure, not a linear one. Note that sound, power and voltage decibels are all different, and many of those use varying reference levels. For sound pressure levels, a 20 dB difference is a ten-to-one SPL change; a 40 dB change is a 100-fold increase. For sound pressure, the common reference level of 0dB is about the threshold of human hearing, at 1,000 Hz.

One decibel is, conveniently, around the smallest perceptible difference to human hearing. It is also interesting that sound is perceived differently than it's actual pressure values. As a rule of thumb, an increase of 10db in measured sound pressure is perceived to be only about twice as "loud." A 20 Db increase sounds about 4 times as loud (instead of 10 times) and a 40 Db increase is perceived to be about 16 times as loud, instead of the 100 times it actually is.

Here are some typical sound pressure levels, and their perceived levels:

Event |

Sound Pressure Level |

Relative Perceived "Loudness" |

Rustling leaves |

10 dB |

1/32nd |

Whispered conversation |

20 dB |

1/16th |

Quiet office interior |

30 dB |

1/8th |

Quiet rural area |

40 dB |

1/4 |

Dishwasher in next room |

50 dB |

1/2 |

Normal conversation |

60 dB |

Baseline |

Dial tone |

70 dB |

2 times |

Car passing nearby |

80 dB |

4 times |

Truck or bus passing nearby |

90 dB |

8 times |

Passing subway train |

100 dB |

16 times |

Loud night club |

110 dB |

32 times |

Threshold of pain |

120 dB |

64 times |

Hearing damage begins to be possible at 140 dB.

Understanding how our auditory sense works can give us greater insight into designing audio alters and notifications. Be mindful of how increased age affects sound wave detection, as well as what levels of loudness are appropriate in our devices.