|

Size: 7701

Comment:

|

Size: 7936

Comment:

|

| Deletions are marked like this. | Additions are marked like this. |

| Line 12: | Line 12: |

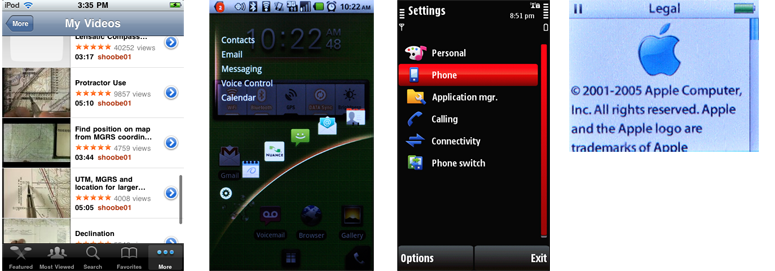

| == Composition Principles == {{attachment:CompositionIntro-Wrapper.png|Just some of the variety -- and similarity -- of annunciator rows, notifications, menus and other device-wide features built into mobile devices.|align=right}} |

|

| Line 13: | Line 15: |

| The invention of the letterpress not only allowed for mass production of existing content, but made it so easy there was demand for more content. And with that content was a need for well-understood page composition principles, not just those handed down secretly by cloistered monks transcribing old works. | |

| Line 14: | Line 17: |

| *** ADD A DISCUSSION OF WHAT COMPOSITION IS. be sure to differentiate between the practice of composition (or composing) and the item of composition, the end result, which is what we mean here. *** | So composition became a process of assembling a layout that consistently arranges components and content on a page. These rules were repeated on all other pages, creating a recognizable system of component relationships that were understood by social reading norms. It helped readers understand why a composition element was arranged within a specific part of the page. They could then expect to find that same element on all other pages with the rest of the book. |

| Line 16: | Line 20: |

| These composition principles made books usable for the first time. Mass consumption meant adding scientific texts, and reading for entertainment, and portable books that could be read anywhere, by anyone. And literacy rapidly grew also, from under 30% to over 90% in the 20th century. Users adapted to the technology as much as it adapted to them. As type principles became standardized, so did binding, type and page sizes, then margins and gutters. Page numbers, titles and chapters on each page followed over time. |

|

| Line 17: | Line 23: |

| == Templates == {{attachment:CompositionIntro-Wrapper.png|Just some of the variety -- and similarity -- of annunciator rows, notifications, menus and other device-wide features built into mobile devices.|align=right}} Before the first Gutenberg Bible, there were perhaps 30,000 books in all of Europe. By 1500, presses had been established in more than 250 places in Europe – 80 of them in Italy, 52 in Germany and 43 in France. Between them, these presses produced about 27,000 editions. Around this date, about 13 million books were in circulation. (Briggs: 2009). |

These standards became promulgated as best practices, and implemented as grids (to which everything is aligned) and templates, which were used on every page to make volumes feel like single works. |

| Line 21: | Line 25: |

| And even more so, books had to become usable for the first time. Mass consumption meant adding scientific texts, and reading for entertainment, and portable books that could be read anywhere, by anyone. And literacy rapidly grew also, from under 30% to over 90% in the 20th century. Users adapted to the technology as much as it adapted to them. As type principles became standardized, so did binding, type and page sizes, then margins and gutters. Page numbers, titles and chapters on each page followed over time. These standards became promulgated as best practices, and implemented as grids (to which everything is aligned) and templates, which were used on every page to make volumes feel like single works. Using templates is essential in mobile design. As designers, we want to create our layouts based on cultural norms of reading conventions and how people process information. We also want to create information that is easily accessed, and easy to locate. Our users are not stationary, or focused entirely on the screen. They’re everywhere and they want information quickly and easy to manipulate. |

Using templates is essential in mobile design. As designers, we want to create our layouts based on cultural norms of reading conventions and how people process information. We also want to create information that is easily accessed, and easy to locate. Our users are not stationary, or focused entirely on the screen. They’re everywhere and they want information quickly and easy to manipulate. |

A Little Bit of History

To many, the year 1440 signified a major shift in global communications. It was during this time in Mainz, Germany, that a goldsmith by the name of Johannes Gutenberg was the first to invent one of the most important industrial machines of the modern period- the printing press.

The printing presses’ use of movable type was inspired by earlier uses found in China, and Japan as early as the seventh century. During this time, they used a method of block printing, which was a carved piece of wood used to print a specific piece of text.

Further advances took place in the 11th century. A Chinese alchemist, Bi Sheng invented a process called movable type. His process consisted of having individual Chinese characters carved on blocks of clay and glue. These blocks were arranged on a preheated piece of iron plate where they were pressed on paper. Bi Sheng’s process was not without fail however. The process was slow, not advantageous for large scale printing, and it’s reliance on clay blocks created problems with the adhesion of ink.

A Revolution Has Begun

Gutenberg’s invention’s advanced the process of movable type further; consisting of individually-cut or -cast letters, sorted onto composing sticks, locked up into galleys, then inked and impressed into paper. This, the invention of modern typography, was the birth of mass printing. It allowed information to move from merely permanent and portable to the first mass media product. It allowed for perfect replication, standardization, and affordable books for the middle class.

Composition Principles

The invention of the letterpress not only allowed for mass production of existing content, but made it so easy there was demand for more content. And with that content was a need for well-understood page composition principles, not just those handed down secretly by cloistered monks transcribing old works.

So composition became a process of assembling a layout that consistently arranges components and content on a page. These rules were repeated on all other pages, creating a recognizable system of component relationships that were understood by social reading norms. It helped readers understand why a composition element was arranged within a specific part of the page. They could then expect to find that same element on all other pages with the rest of the book.

These composition principles made books usable for the first time. Mass consumption meant adding scientific texts, and reading for entertainment, and portable books that could be read anywhere, by anyone. And literacy rapidly grew also, from under 30% to over 90% in the 20th century. Users adapted to the technology as much as it adapted to them. As type principles became standardized, so did binding, type and page sizes, then margins and gutters. Page numbers, titles and chapters on each page followed over time.

These standards became promulgated as best practices, and implemented as grids (to which everything is aligned) and templates, which were used on every page to make volumes feel like single works.

Using templates is essential in mobile design. As designers, we want to create our layouts based on cultural norms of reading conventions and how people process information. We also want to create information that is easily accessed, and easy to locate. Our users are not stationary, or focused entirely on the screen. They’re everywhere and they want information quickly and easy to manipulate.

The Concept of a Wrapper

Throughout this book, we discuss patterns, from which can be made the very specific templates which can be used for any particular product or project.

The templates which are used across a product, on most every page of a website or application, we call a "wrapper" because they enclose (wrap around) all the other components and the content.

Considering design from the wrapper down allows:

- The designer to organize information within a consistent template across the OS.

- Information to be organized hierarchically on a page.

- The user to identify the organizational structure quickly, increasing learnability while decreasing performance error.

Context is Key

Wrappers must be designed based on the content and the context of use as much as any other part of the product. A wrapper for a mobile phone application will be quite different from that for a portable GPS, or a kiosk. When determining which information belongs in the wrapper you must decide on a multitude of things regarding context of use:

- The technological, functional, and business requirements and constraints.

- Where the context of use is occurring.

- The goals of the users.

- Which tasks are needed to achieve those goals.

- What types of information must be displayed to achieve that goal or task.

Patterns For Composition

Using appropriate and consistent wrappers will create mappings and affordances that will allow for positive user experiences. Within this wrapper chapter, the following patterns will be discussed, based on how the human mind processes patterns, objects, and information:

Scroll-When information on a page exceeds the viewport, a scrollbar control may be required to access the additional information. Scrolling of information should most always occur along one axis, except in rare cases.

Annunciator Row– Displays the status of hardware features on the top of each page. The status of functions that may be displayed are: radios, input and output features, and power levels.

Notifications– When an alert is requiring user attention, a notification will occur in some form of visual, haptic, or audible feedback. These notification displays must allow for user interaction.

Titles– Pages, content, and elements that require labels should use titles. These titles should be horizontal, consistent in style, and follow guidelines of legibility and readability.

Revealable Menu– Displays additional menus that are not immediately apparent. A gesture, soft-key, or on-screen selection will cause these menus to immediately display on screen.

Fixed Menu - Presents an always visible menu or control that is docked to one side of the viewport. This menu is consistently placed throughout the application. These interactive controls are most likely icons with textual coding.

Home & Idle Screens– Are used as display states when either a device is turned on or an application has exited, timed-out, and retuned to a device-level menu display.

Lock Screen- Mobile devices use this display state to save on power consumption. When necessary, the applications sleep state may become locked to protect the security of user inputted data. Additional user interaction is required to exit out of the lock screen.

Interstitial Screen– Is used primarily as a loading process screen during device or application start-up. Wait indicators may be used to show loading progress.

Advertising – When advertising is used within the mobile application, it must be distinct, and not affect the user experience. Obtrusive advertising could prohibit the user from achieving his task-based goals. Advertising must adhere to the specific guidelines set by the Mobile Marketing Association.