What a Mess!

Whether you’re a student in college, a design professional, or an author of a book, you have all experienced the clutter of notes, reminders, memos, drawings, and documents scattered across the surface of your desk. There comes a point in this chaotic, unorganized display, when your tidy instinct begs for some order.

If you're lucky, you quickly find materials you can use: a binder, file folders with the colored tabs, paper clips, even a stapler. You grab the content, sort and filter as a means for organizing and making order. As you organize, you may classify the data by such lateral relationships as:

Nominal

- Using labels and names to categorize data

Ordinal

- Using numbers to order things in sequence

Alphabetical

- Using the order of the alphabet to organize nominal data

Geographical

- Using location, such as city, state, and country, to organize data

Topical

- Organizing data by topic or subject

Task

- Organizing data based on processes, tasks, functions, and goals

Having now integrated your organizational skills with those office supplies, you can mar- vel at your clean desk. On its surface lay a faceted arrangement of folders. Each folder, containing related content, is clearly labeled with colored tabs to allow for quick and easy access.

Navigation Structure

As discussed in Chapter 2, we understand the importance of organizing an information structure across a single page, or an entire OS. To recap, we know that there are two main types of organization with information architecture: Hierarchy

- Organizes content based on top-down, parent-child relationships.

Faceting

- Organizes based on information attributes without imposing any parent-child relationships. The structure is based on heterogeneous content, with each item sharing the same level—being just as “important”—within the information architecture.

Lateral Access and the Mobile Space

Content across a device OS must be organized and designed to follow a consistent information architecture to ensure a positive user experience. However, when considering mobile devices, the potentially smaller displays play a significant role in determining how this information architecture is designed for interaction. Smaller screen sizes affect the amount and type of content presented, and the user’s ability to successfully search, select, and read this information. To account for this, consider presenting the information laterally, at the same tier level in the information architecture.

Use the appropriate widget to provide access to the information, and to make the relation- ship between items clear.

There are several reasons to use lateral access widgets across the mobile space:

- Mobile displays can be much smaller than a PC, reducing the amount of information shown on a viewport’s current state. Unlike PCs, where information is designed for 1024 x 768 resolution, common smartphones still (in 2011) have screen resolutions at 320 x 480 pixels.

- Even for larger screen devices, pointing is often very coarse, with the common use of capacitive touch. Many interactive items cannot be as small as they would be on a similar-size computer with a mouse or similar interface (trackpad, trackball, pen, etc.). In addition, the user’s finger and hand may occlude information during interac- tions, which may be much of the time the device is in use.

- Globally, feature phones still make up about 80% of the mobile market. These devices have a common resolution of 240 x 320 pixels, though some can have much smaller screen resolutions, down to 128 x 176 pixels.

- Because the screen real estate is so valuable, it’s important to prioritize features and content related to the user’s high-level goals.

- A mobile user’s attention is competing with all the stimuli in the surrounding envi- ronment. Therefore, the access to the content must be detectable, even at a glance, and afford its function appropriately.

- According to Fitts’s Law, there is a direct correlation between the size of the target, its distance from the user, and the amount of time it takes to select it. Therefore, a smaller display requires larger buttons for gestural interaction—which, in effect, will reduce the amount of content that can be placed on the screen.

Use of lateral access affords the following benefits:

- Categories of information do not have to be labeled within a long list, or as flags on arbitrarily listed items.

- Lateral access limits the number of levels of information a user has to drill through to access priority information.

- Lateral access can reduce “pogo sticking,” or constantly returning to a main page to drill into subsidiary pages, searching for the right section.

Follow the Principles of Wayfinding and Norman’s Interaction Model

As you are now aware, the size of mobile displays can greatly influence how you should organize and design your content. To make sure your users can navigate across this content, consider applying research-based frameworks tied to wayfinding and Donald Norman’s Interaction Model.

Wayfinding

In the introduction to Part III, the principles of wayfinding are discussed in detail. You can apply certain wayfinding principles to lateral access widgets to ensure that your user can navigate across content with ease. Districts

- Within the viewport, sections of information that are grouped or bounded by visual elements that follow the laws of proximity will be perceived as being related and separate from other components.

Tabs

- Place related tabs adjacent to one another to define a perceived group. These tabs may share common visual design elements, such as size, shape, color, and form. If you are using multiple groups of tabs, make sure these are clearly distinguishable from other tab groups. Selected tabs must be bound to the related area of content.

Pagination controls and indicators Most often these widgets should be placed immediately above and below the content unique to the page. Another option is to anchor the widget (in the title bar, for example), so it is available at all points on the page. If the page does not scroll, a single fixed-location item logically becomes an anchored widget. Landmarks

- Distinct visual objects that are easily detected and identified from other elements will likely be perceived as reference points. In the mobile space, landmarks can aid the user in quickly finding key navigation features, as well as providing a reference to their position within the browsable content. When designing lateral access widgets as landmarks consider shapes that are well understood by the user and afford the correct action.

Norman’s Interaction Model

As Donald Norman said, “Make things visible!” (Norman 1988). Lateral access elements must follow the principles of legibility, readability, and conspicuity discussed throughout this book. Consider the principles discussed in the following subsections.

Feedback

Feedback is a noticeable and immediate response to a direct interaction. Using feedback appropriately confirms to the user that his action took place. Feedback can be visual, haptic, and audible. If feedback is too delayed or does not exist, the user will become frus- trated or lost after the action is completed.

Even if there is essentially no delay in the actual loading of the new content, explicit feed- back may be needed to make it clear, if the change is not clear at a glance.

Consider how feedback can be applied to: Tabs

- An immediate response must occur after a user selects tabs. The selected tab may change color and size and will display its related content in the viewport. Adjacent tabs that are not selected must remain unaffected. Be sure to follow conspicuity guidelines when selecting appropriate colors to contrast with the background.

- Whether you are peeling a back corner to reveal the page underneath, or rotating an object, feedback must occur to indicate the action was successful. As discussed in detail in Part I, images are transformed incrementally within our visual perception process. When we see an object move and transform its shape in incremental steps, we have an easier time understanding that the two objects are related or identical. Therefore, use appropriate transition speeds throughout the entire action.

- Feedback can be used to display indications of page jump. Those pages not accessible due to current context can be grayed out. For example, “Back” or “First page” links should be visible but inaccessible when the user is already on the first page.

Mapping

Mapping describes the relationship between two objects and how well we understand their connection. We’re able to create this relationship when we combine the use of our prior knowledge with our current behaviors. To quickly recall these relationships, we de- velop cognitive heuristics, or cultural metaphors. These metaphors reinforce our under- standing of the relationship of the object and its function.

Some common metaphors you can use to access information on mobile devices are: Tabs

- Tabs are understood in principle to correlate to the file folder tab. We expect this tab to be selectable and an identifier of a folder that contains related content. If we see one tab, we will expect to see adjacent tabs that are separating additional content. Too many grouped tabs, however, will cause our users to become cognitively overloaded during the decision making process, thus resulting in slower performance and user frustration.

Cubes

- Cubes show content on one or two faces, and will be expected to have content on all other sides that share the same axis. Users will expect faces to rotate. Constrain the rotation to one axis; otherwise, users will become frustrated with their inability to quickly navigate and correctly select the content. Animation of the rotation from one face to the other must be provided. Otherwise, the user may not know her current selection’s position on the cube.

Peeled corners

- Pages that are slightly peeled back are understood in principle to correlate to pages in a book. We expect access to the pages underneath the top layer. A gestural interaction that allows for turning the page will be expected. Animate the transition from one page to the next.

Other 3D effects

- Aside from multisided shapes, effects such as shadows and transparency can be used to simulate layers and depth. The user will understand that information can occupy virtual space, appearing modally in front of other layers, while hiding others.

Constraints

Restrictions on behavior should be appropriately implemented to eliminate or reduce performance error while laterally accessing content. Consider using the boundaries of the display (edges and corners) during gestural and scroll-and-select navigation. The edges and corners provide an infinite area over which to move our fingers or cursor. This can significantly reduce the amount of time it takes to navigate across pages. Consider this effect when using a circular or closed navigation structure. Circular navigation

A key tactical consideration, mentioned several times in the patterns, is whether browsable data sets are “circular” or “dead-end”. Circular lists simply go around and around. When the user is at the “last” item in a list, continuing to view the next item will display the first one in the list. This is useful for faceted views or other cases where the ordering is unimportant. Consider integrating the Location Within widget to indicate current position.

Closed navigation

For dead-end lists, there is a definitive start and stop, and (aside from links such as “Back to top”) there is no way to go to the other end. These are useful for information with a very ordered, single-axis display. Most hierarchies and much date-sorted information should display like this. An example is a message list that starts with the most recent message. Consider integrating the Pagination widget to indicate current position.

The severity of your constraints will vary widely depending on the criticality of the fea- ture. An entertainment application may be designed for delight, and be expected to draw attention and be used while still; therefore, it has very few constraints. An SMS applica- tion could be used by anyone, anywhere, under any conditions, so it must be easy to use above all other considerations.

Medical and public-safety applications may have additional constraints. Even consumer device features may have legislative or regulatory constraints that must also be addressed.

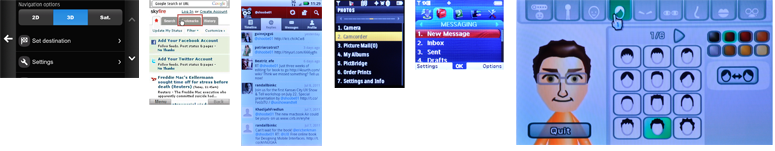

Patterns for Lateral Access

Using appropriate and consistent lateral access widgets will provide an alternative way to present and manipulate content serially. Within this chapter, the following patterns will be discussed, based on how the human mind organizes and navigates information:

- Based on the concept of file folder tabs, and used to separate and clearly communi- cate sets of pages or features at the same level in the information architecture. See Figure 5-1.

- An organic and animated representation of a page being flipped over to reveal a sec- ond page behind it.

- Display an alternate view to the content on the page using 3D graphics. When device gestures or viewer movements are used, the items affected will follow the presumed physics or correctly represent the space they occupy.

- Serially displays a location within a set of pages, and offers the ability and function to navigate between pages easily and quickly.

- Uses an indicator to show the current page location within a series of several screens of similar or continuous information. This is presented with an organic access method.

Discuss & Add

Please do not change content above this line, as it's a perfect match with the printed book. Everything else you want to add goes down here.

Examples

If you want to add examples (and we occasionally do also) add them here.

Make a new section

Just like this. If, for example, you want to argue about the differences between, say, Tidwell's Vertical Stack, and our general concept of the List, then add a section to discuss. If we're successful, we'll get to make a new edition and will take all these discussions into account.